A Silver Lining From Comic Book Burnings and Censorship in Postwar America: Book Censorship News, December 19, 2025

⚓ Books 📅 2025-12-19 👤 surdeus 👁️ 11It regularly surprises people to learn that America’s history includes a period of time when books were burned. The surprise comes in part because there’s a lack of knowledge about how book censorship has been fundamental in American history and in part because the American government spent a lot of time, money, and energy delivering propaganda during World War II about Nazi book burnings that was intended to drum up patriotism. Americans wouldn’t burn books like Nazis would, would they?

They would. In fact, they’d do it in the years following the end of World War II.

The target? Comics.

Last week kicked off the first in a trilogy of posts focused on comic book censorship in America. History professor and comic censorship scholar Brian Puaca talked about what made burning comics a seductive activity in post-World War II America. This week, he is back to offer a more optimistic read on comics censorship through that same period and on into our present day.

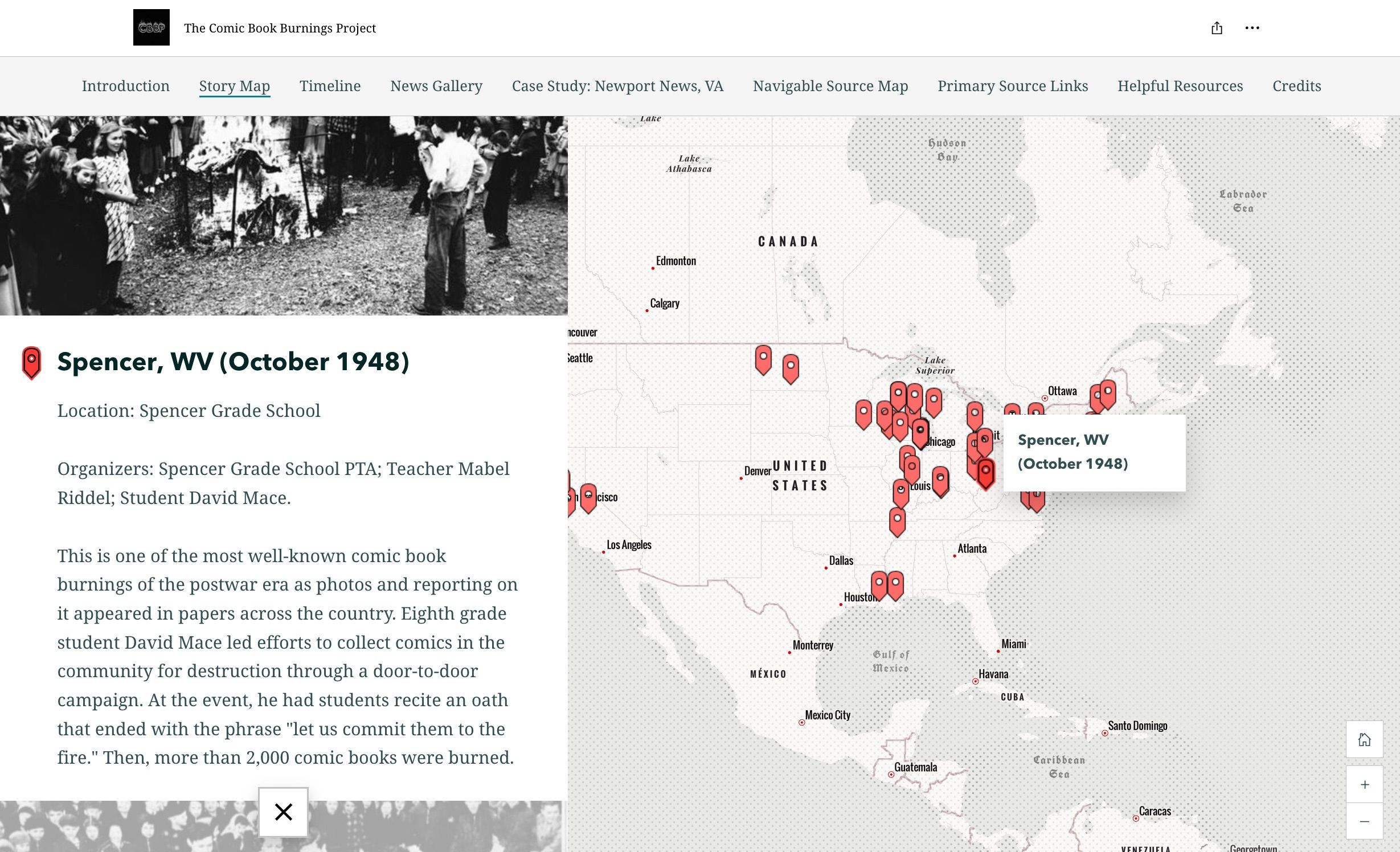

Brian Puaca, Professor of History at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, reached out to me earlier this year and shared with me a project he’d been working on called the Comic Book Burnings Project. As the title suggests, it’s a look at how Americans found community through comics burnings in post-war America. It’s an incredible work of scholarship, including timelines, primary sources, maps, and images from this era of nationwide censorship.

***

|

Searching for a Silver Lining: Comic Book Burnings and Censorship in Postwar America

As the year winds down and we look forward to the holidays, many of us return to annual rituals that mark our entry into a new year. One of those yearly traditions, which I approach with a mix of trepidation and resignation, is the release of the American Library Association’s Top 10 Most Challenged Books of the Year list.

Just about every year, two or three comics titles land in the top ten. Last year it was Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer and Mike Curato’s Flamer. The controversy surrounding these graphic novels reflects larger social debates about LGBTQ+ identities and politics. Ten years ago, it was Craig Thompson’s Blankets and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, and these works were criticized for violence, nudity, and “graphic images.” If history is any guide – and as a historian, I have to believe that it is – we’ll see a few comics works on the forthcoming list for 2025. Notably, we’ll have to wait a little longer than January for the list, which is released as part of National Library Week in April.

Comics have long been the target of zealous censors. Just as it has been the case in recent years, so too have comics been linked to the broader social concerns and anxieties of Americans in decades past. Most notably, in the years after World War II, a generation of teachers, parents, intellectuals, politicians, clergy, civic leaders, medical professionals, and journalists linked comics to the social fears of the time: juvenile delinquency, “deviant sexuality,” and violence. To combat these dangerous ideas circulating in the hands of millions of young readers, they organized a variety of initiatives to censor content, ban sales, remove publications, and, in extreme cases, destroy objectionable works.

The most extreme actions to protect young readers from the dangers of comics were undoubtedly comic book burnings. Beginning in the same year that the United States defeated the most infamous book burners in modern history, more than 50 such events took place across the country. From California to Massachusetts, and from Michigan to Louisiana, this movement to destroy comic books enjoyed widespread support across American society. The anti-comics crusaders were: men and women; boys and girls; young and old; Black and white; urban and rural; devout and agnostic. For some it was a religious mission; for others it was sincere (if misguided) patriotism; for everyone involved it was a way to protect the country’s youngest citizens.

It is a dark, and relatively unknown, chapter of America’s postwar history.

The story of comic book burnings is unsurprisingly a tale of scapegoating, social panic, and Cold War insecurity. Yet at the same time, there were also displays of reason, restraint, and engaged citizenship. Part of the story of comic book burnings is the fact that some were canceled. In many cases, even at the height of McCarthyism in the 1950s, thoughtful and courageous Americans challenged the idea that physically destroying literature was a solution to any of the country’s problems. In the instances when burnings did take place, they were often contested. For example, many newspapers authored editorials that cast doubt on these spectacles. Even when they sympathized with the concerns raised by organizers, most media outlets that commented directly on comic book burnings typically criticized their means. And in some cases, organizations such as the ACLU and the American Book Publishers Council successfully challenged planned burnings as inconsistent with American values.

As a historian reflecting on a history comic book burnings from the vantage point of today, a few developments seem particularly striking. First, one cannot help but be astounded by the widespread embrace of the comics medium by libraries and educators in the past few decades. The fact that graphic novels regularly land on the Top 10 Most Challenged list is obviously upsetting, but it can also be viewed as a sign of how far comics have come in a relatively short time. The dramatic growth of comics and graphic novels in public and school libraries is indeed an extraordinary achievement. Second, comics continue to serve as a flashpoint for broader social fears in America – from violence, obscenity, and drug use to nudity, sexual promiscuity, and gender identity. Yet at the same time, comics no longer carry the connotation of juvenile literature. As has long been the case with film, there is now widespread recognition of the difference between the genre and the medium. This has played an important, if subtle, role in responses to critics demanding the removal of certain works. Third, releasing the Top 10 list as part of National Library Week highlights the perpetual threat of censorship. While we may no longer be burning comic books, we read regularly about those that would remove access to content they find objectionable for all other readers. The annual publication of this list keeps us informed and on guard.

That the Top 10 list is published as part of National Library Week is especially remarkable in that it illuminates dramatic changes in the professional field of Library Sciences. In November 1954, an elementary school in Newport News, just three miles from my campus, organized an anti-comics crusade led by students, teachers, and the PTA. These groups collaborated to collect objectionable comics, encouraged local businesses to display posters supporting the campaign, and held a pageant featuring characters from “good books.” The week of festivities culminated in a comic book burning outside the school at which a student government officer and the Assistant Fire Chief ignited the blaze. Most distressing of all, these events took place as part of the school’s celebration of National Children’s Book Week.

And so, librarians, who once helped organize the burning of comics in many schools across the nation, now find themselves on the front lines working to ensure that they remain in their collections. There’s certainly a silver lining in that.

Book Censorship News: December 19, 2025

As the year winds down, expect these roundups to be a little shorter than usual. That’s not a reflection of a slowdown in extremism when it comes to book censorship or library attacks. It’s a reflection of the holidays and school breaks in the U.S.

- Here’s an example of a great letter to the editor about the lies being spread over why books are inappropriate and need to be banned.

- Curious what’s going on with the lawsuit over Iowa’s “Don’t Say Gay” book ban law? The latest is that it’s still null but the case remains in appeals court.

- “Dozens of parents and community members have signed up to help track book bans across the state, by learning how to file public records requests and keeping tabs on school districts. The Texas Freedom to Read Project launched the grassroots campaign this month after state lawmakers passed new book banning policies. The goal is to create a more up-to-date, accurate picture of what kinds of books are being banned and where it’s happening. With over 1,200 school districts in Texas, the organization is building a team of community volunteers statewide to help gather information.” Great piece on what the Texas Freedom to Read Project is doing to track book bans statewide.

- The latest from Bellbrook Sugarcreek School District (OH) and their book ban policy (see here).

- A teen writes a fantastic editorial about how he feels seeing his New Hampshire school ban The Perks of Being a Wallflower after a single parental complaint. “I am open with my sexuality to anyone who asks in the hallways of Merrimack Valley, which leads me to wonder: Should I be removed from the school if parents find the topics I speak about inappropriate? Is this removal of a LGBTQ+ narrative in the school a way to keep students “pure,” or a way to ensure those who feel morally superior retain absolute control?”

- It is possible we’ll see Iowa republicans once again try to deny funding to public libraries for not banning books they don’t like. Read this editorial–it’s really good. The GOP doesn’t like not being able to make everyone obedient to their whims.

- Families in North Little Rock School District (AR) are unhappy the district simply removed 50 books from one of the district’s reading apps. Most are, of course, LGBTQ+ books.

- How Ulysses Was Almost Banned By the State of New York.

- Here are the top 52 books banned since the rise in book censorship really took off in 2021.

- Keep an eye on Mesa County, Colorado, public libraries. The board just saw the appointment of two extreme conservatives with little notice to the public.

- What happens when two rockstar librarians–Suzette Baker and Amanda Jones–collaborate? This really essential piece in TIME Magazine about what the Supreme Court’s decision not to hear the Little vs. Llano County case means for public libraries in three US states.

- Even thought republicans in New Hampshire tried to override the (repulican) governor’s veto on their book banning bill, they did not garner the support to revive the bill. The freedom to read continues in the state.

- West Shore School District board (PA) tried to pass a book ban bill before the far-right members who lost their seats are replaced by newly elected members. It did not pass, as it’ll be tabled for when the new board is in.

- The Garfield County Public Library District Board of Trustees (CO), which has been among the districts with a long history of book censorship and attacks on the freedom to read, has four open board seats. Here are the answers from potential candidates about why they’re running and their beliefs on restricting books in the library. Some of these are deeply concerning.

- PEN America has released a report on the top 52 books banned in American schools since the rise of coordinated book bans began in 2021.

Don’t miss the news we covered here at Book Riot this week, including the censorship of “gender ideology” at York Public Library (SC) and a collaborative piece on the trends in book censorship in 2025.

🏷️ Books_feed